Bayesian Objectivism or Are We Sure We Can Trust Those Damn Scientists?

- Joseph James

- Sep 1, 2021

- 7 min read

“While differing widely in the various little bits we know, in our infinite ignorance we are all equal.”

― Karl R. Popper

The point of this article is as follows: when a scientist makes a claim, how do we know they can be trusted? This question is more relevant than ever in the days of Fake News and Fox News, however the mistrust of science has existed for as long as there has been scientists. Below, we will hear from the great philosophical defenders of science, who will hopefully provide some clarity on whether science is trustworthy. First, I will summarise a key argument in James Franklin’s defence of science, I will then introduce Karl Popper’s argument on scientific logic and put it head-to-head with Franklin’s ideas, and finally I will wrap up with some words of advice for the reader.

In “What Science Knows and How it Knows it”, James Franklin sets out to provide an explanation as to “why science is rational”. What follows is a defense of the scientific method and an explanation as to why the reader can trust scientific conclusions. We will follow the beginning of Franklin’s rigorous defence of science, and explore his thoughts on Bayesian Objectivism and how it holds that “the relation of uncertain evidence to conclusion is one of pure logic.”

Franklin begins with a most fundamental question, how can we be sure of anything? He gives an example statement: “All ravens are black” and promptly waves away certain problems regarding our perception of reality and almost semantic objections to our definition of “raven” in order to reach to the crux of his argument, the problem of induction.

The “problem of induction” is an age-old issue in the philosophy of science. The problem is as follows: If an event yields the same outcome repeatedly in the past, is it logical to conclude that the same event will yield the same outcome in the future? Franklin gives a historical example to illustrate the problem. “All swans are white” was a simple conclusion reached based on the evidence that all observed swans up to a point in time were white. In 1967 a group of black swans were observed and the conclusion that “All swans are white” was shown to be false. It is tempting, upon reading this example, to abandon all inductive reasoning, as it is clear that conclusions based on observed data are always uncertain, unless all observations have certainly been made. In defense of the scientific method, Franklin attempts to prove that conclusions reached from inductive knowledge are logically justifiable.

I think it is important to define what we mean by the word ‘logically’. This is a side-step that Franklin takes briefly when he argues the fallaciousness of the word ‘logic’ only applying to cases where it is impossible for a given premise to be false. When writing the phrase ‘we can logically conclude’, we mean something synonymous with ‘it is correct to conclude’. Continuing with this definition it is possible for us to circumvent the thesis that ‘all logic is deductive’ and we are able to make claims for the existence of a non-deductive logic, provided that it is possible to convince the reader that we can correctly reach conclusions using non-deductive means.

“Objective Bayesianism holds that the relation of uncertain evidence to conclusion is one of pure logic.” To put it another way, it is correct to formulate conclusions based on observed evidence. For example, if we have only ever seen white swans then it is perfectly logical to conclude that all swans are white. This is a conclusion that we know to be false, however this does not mean that it was an illogical conclusion. It only became an illogical conclusion to hold once we acquired additional data. We must revisit our definition of ‘logical’ at this point and add that when writing the phrase ‘we can logically conclude’, we actually mean something synonymous with ‘it is correct to conclude, even if the conclusion is incorrect’

To argue for Bayesian Objectivity we are arguing that it is logical to make conclusions that may be false. Franklin makes this argument from a statistical standpoint. Let’s say 99.9% of men are mortal and Socrates is a man, then we can say with confidence that Socrates is mortal. Our confidence of this hypothesis will only increase as we observe more and more mortal men, increasing our certainty that Socrates is a mortal by increasing the probability that he is mortal.

I could flip a coin 10 times and find that it lands heads 7 of those times. It is possible to then logically come to the incorrect conclusion that a coin will land heads 70% of the time, however I have not observed enough events for me to have a high level of confidence in my claim. If Bayesian objectivity works then I will keep running the experiment and collecting more data, amending my hypothesis as I go, and ultimately I should tend towards the ‘correct’ conclusion. Franklin is arguing that this method is entirely logical.

Only one question therefore remains: how much evidence is necessary before we can be confident in a conclusion. Bayesian Objectivists appear to hold the belief that it is logical to form a conclusion from a single observation, admitting that it would be a very uncertain conclusion. Additional agreeable observations will make a given conclusion more certain with the limit tending to absolute certainty once all possible observations have been made.

We are discussing a concept that lies at the core of modern science. By the scientific method, an observation is made and a hypothesis is formed around this observation. Additional observations are then made which will either strengthen or disprove the hypothesis. In natural science it is impossible to make all observations due to the infinite nature of the universe, as such we are never 100% certain of any hypothesis in physical science. Allowing us to relate experimental observation to a hypothesis and accepting that the hypothesis is falsifiable until all observations have been made enforces a humility in science, Bayesian objectivity will never allow a hypothesis to claim to describe the world with complete accuracy and because of this scientists can never claim to have knowledge beyond what is shown by empirical observation. We can never say “we know X.”, we must say “we think X based on all available evidence.”

I will now analyze Franklin’s critique of Popper’s ideas. Franklin begins by poking fun at Popper. He comment on the irony of a book titled “The Logic of Scientific Discovery” that details how scientific discovery is devoid of logic. Even though this is Popper’s thesis, he still thought of himself as being a defender of the scientific method.

Popper did not respect theorists who would only use their theory to attempt to explain past events. Popper felt that a serious theorist should make future predictions from their theory and risk being disproven, this is the only way to test a scientific theory. Franklin, Popper and I agree on this point: any good theory should be able to predict the future, but Franklin does not agree with the extrapolation that Popper made from this point.

Popper was a firm believer that true logic could only be deductive logic, as he learnt from Hume. So he concluded that any theory that could be proved false is not science, as it is not founded in deductive logic. However, Popper’s idea is much muddier in the real world. Franklin thinks it is often impossible to find a logical contradiction in the natural universe. For example, Newton’s theory of Gravity is near confirmed by observations of planetary elliptical orbits, but the theory is not incompatible with an observation of square orbits, if we have some sort of auxiliary hypothesis with which to connect the two. Franklin says in the natural world are always able to find some far-fetched and unlikely link between two seemingly inconsistent hypotheses.

Franklin also points out another problem in Popper’s theory: that some hypotheses are impossible to falsify due to their wording. For example “Most swans are white” is not falsifiable because the statement is logically compatible with any relative frequency of white-ness in observed swans. Popper was aware of this problem and proposed replacing the standard logical questions with what Franklin describes as “sociological entities”[1] in order to get around, but not solve, the issue.

The next issue is the biggest for Franklin. He believes that if a theory has survived falsification after rigorous testing, it should be deemed more creditable. However, if we deny the existence of probabilistic logic as Popper does, these surviving theories are just as irrational and unbelievable as their disproved kin. Franklin feels that this problem puts the biggest nail in Popper’s irrational coffin.

However, I feel Popper’s original idea that “a theory must make future predictions and risk being disproven” works well with Bayesian Objectivity. The riskier the prediction, the lower the chance of theoretical success, and therefore a successful prediction makes a theory more credible and the more unlikely the predicted event was, again the more credible the theory becomes.

Popper’s thoughts on logic are taken as a message to scientists that hypotheses must be rigorously tested and must always be taken to be uncertain when based on a finite number of observations. The core of Popper’s theorization – that a hypothesis is no more probable even after rigorous testing – is treated by Franklin and the scientific community as “a minor technicality of little interest.”

Hopefully this article offers some interesting food for thought. I strongly believe that the ideas of Popper and Franklin should not be reserved for university philosophy courses, but they should enter the mainstream so please mention this article next time you’re at a dinner party! If you’re like my mum and you only ever read the first and last paragraph of any article (hi mum!) I have consolidated the 4 key insights here:

Never trust a theory that cannot be disproven – as that is not science, it is religion.

Scientific theories should not only explain past events, they must also make correct predictions about the future.

How do we know if a scientific theory is credible? It is a function of the number of correct predictions made as well as the improbability of those predictions coming true.

Scientists (especially those from the messy life-sciences) can very rarely observe every relevant data point. Therefore, we can never say “we know X”, we must always conceded “we believe X based on all available evidence”.

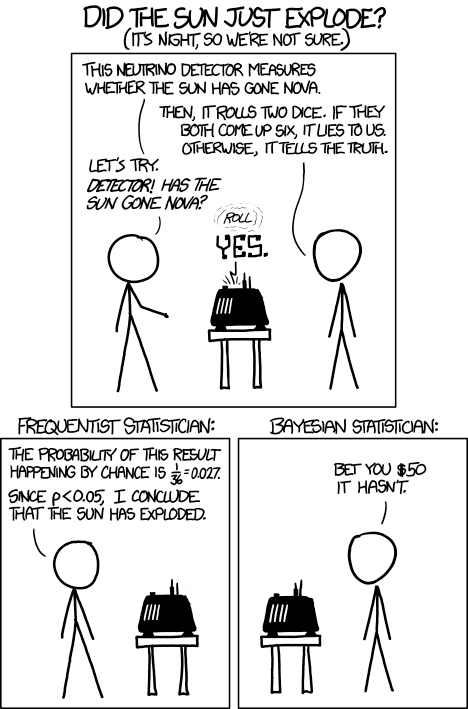

Now here’s the mandatory relevant XKCD:

Comments